Chaos in the Atlantis basin

A myriad of terrain types are found across the Terra Sirenum region in the southern highlands of Mars. Within the Atlantis basin, a complex and rugged landscape spread across roughly 200 kilometres known as Atlantis Chaos just begins to exemplify the broad diversity of geological processes that occurred in this relatively small area. The traces left behind by these events are clearly visible in this image mosaic, which was created from four images acquired by the High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) carried by the ESA Mars Express orbiter and operated by the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR). The views shown here were created by the Planetary Sciences and Remote Sensing group at Freie Universität Berlin. The systematic processing of the HRSC image data was carried out at DLR.

Atlantis Chaos perspective

• Fullscreen, Pan and Zoom • Download high resolution

Disrupted landscape

Atlantis Chaos stands out for its highly disrupted landscape structure consisting of several hundred light-colored small peaks and mesas distributed across a nearly circular lowland plain. These are most likely remnants of outliers. Originally, it may have consisted of sedimentary deposits that were carried into the basin by the wind and subsequently altered by the influence of water. Here on Earth, this kind of sediment layer is referred to as 'loess'. In China, there are loess deposits with thicknesses of up to 400 metres.

Atlantis Chaos color mosaic

• Fullscreen, Pan and Zoom • Download high resolution

Evidence of a large body of standing water

The Atlantis basin likely owes its existence to an asteroid impact that took place in the early history of Mars. Now, the circular profile of what could be the crater rim is barely detectable. There are several other large basins in Terra Sirenum – most likely created by asteroid impacts as well. Many scientists suspect that standing water once filled these partially connected crater depressions – the hypothetical Eridania lake, which may have covered an area of over one million square kilometres.

Many questions about the geological history of the region remain unanswered. For instance, discussions continue on whether the possibly water-filled interconnected crater depressions of Terra Sirenum were also the source of a river that etched the striking Ma'adim Vallis into the Martian Highlands. It is 700 kilometres long and up to two kilometres deep, similar to the Grand Canyon in the western United States, and feeds into Gusev Crater, the area in which the NASA's Mars Exploration Rover Spirit carried out its research mission from 2004 to 2011.

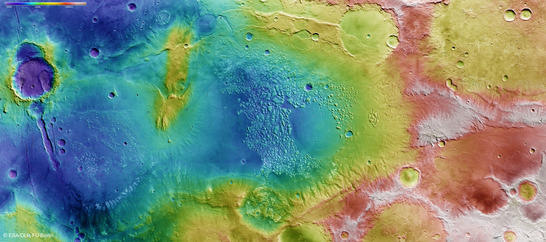

Atlantis Chaos color coded digital terrain model

• Fullscreen, Pan and Zoom • Download high resolution

3.8 billion-year-old clay minerals

The landscape shown here extends for about 600 kilometres in the north-south direction and 250 kilometres from east to west; it is roughly two and a half times the size of Austria. A 'channel' connects the Atlantis basin to another basin located further south (to the left in images 2, 3 and 4) with a diameter of 175 kilometres. Chaotic remnants of a number of former mountains are spread out across this circular depression, covered with light-colored material like those in the neighbouring Atlantis basin.

Spectrometers fitted to Mars Express and other spacecraft in Mars orbit have determined that these light-colored deposits consist of phyllosilicates similar to those found in various types of clay on Earth. Their crystalline structure offers space to accommodate water molecules and hence indicates the presence of water in this area. It appears likely that the loess sediments deposited by winds were altered after coming into contact with water. Their stratigraphic position is the same as that of the clay minerals in other sub-basins of the hypothetical Eridiana lake and their age is estimated at 3.8 billion years.

Channels carved into the basin slopes provide further evidence for the existence of water. Additional sediments may have been washed along these channels and into the floor of the crater basins. The ridges that bound the two basins to the east (lower edge of images 2, 3 and 4) display extensive stratification running from north to south. A large fault zone in the south of these images, running through one of the impact craters, is an additional conspicuous feature. The edges of this more recent, relatively well-preserved crater also display layers of rocky sediments, together with landslides and, in one area, strikingly distinctive channels.

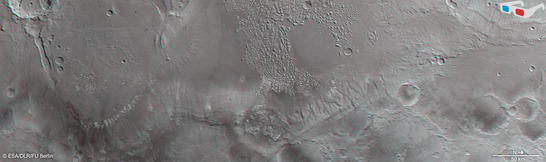

Atlantis Chaos anaglyph

• Fullscreen, Pan and Zoom • Download high resolution

Image processing and the HRSC experiment on Mars Express

The pictured scene was assembled from four strips of images acquired by the High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) during orbits 6393, 6411, 6547 (2008/2009) and 12,724 (2014). The centre of the image is located at approximately 34 degrees south and 183 degrees east. The image resolution is roughly 14 metres per pixel. The color plan view (image 2) was acquired using the nadir channel, which is directed vertically downwards onto the surface of Mars, and the color channels; the oblique perspective view (image 1) was derived from data acquired by the HRSC stereo channels. The anaglyph (image 4), which produces a three-dimensional impression of the landscape when viewed through red-blue or red-green spectacles, was derived from the nadir channel and one stereo channel. The color-coded plan view (image 3) is based on a digital terrain model of the region from which the landscape topography can be derived.

The High Resolution Stereo Camera was developed at the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) and built in collaboration with partners in industry (EADS Astrium, Lewicki Microelectronic GmbH and Jena-Optronik GmbH). The science team, which is headed by principal investigator (PI) Ralf Jaumann, consists of 52 co-investigators from 34 institutions and 11 countries. The camera is operated by the DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin-Adlershof.